Bucks County Playhouse

The Bucks County Playhouse is located in New Hope, Pennsylvania, at the site of a former grist mill. The original structure was built in 1790. When owner Benjamin Parry rebuilt the Hope Mills after it burned down, he renamed it New Hope Mills, which inspired the village to change its name from Coryell’s Ferry to New Hope. Facing demolition in the 1930s, the site was saved when a small band of artists helped rally the community to renovate it as a theater. The Bucks County Playhouse opened on July 1, 1939.

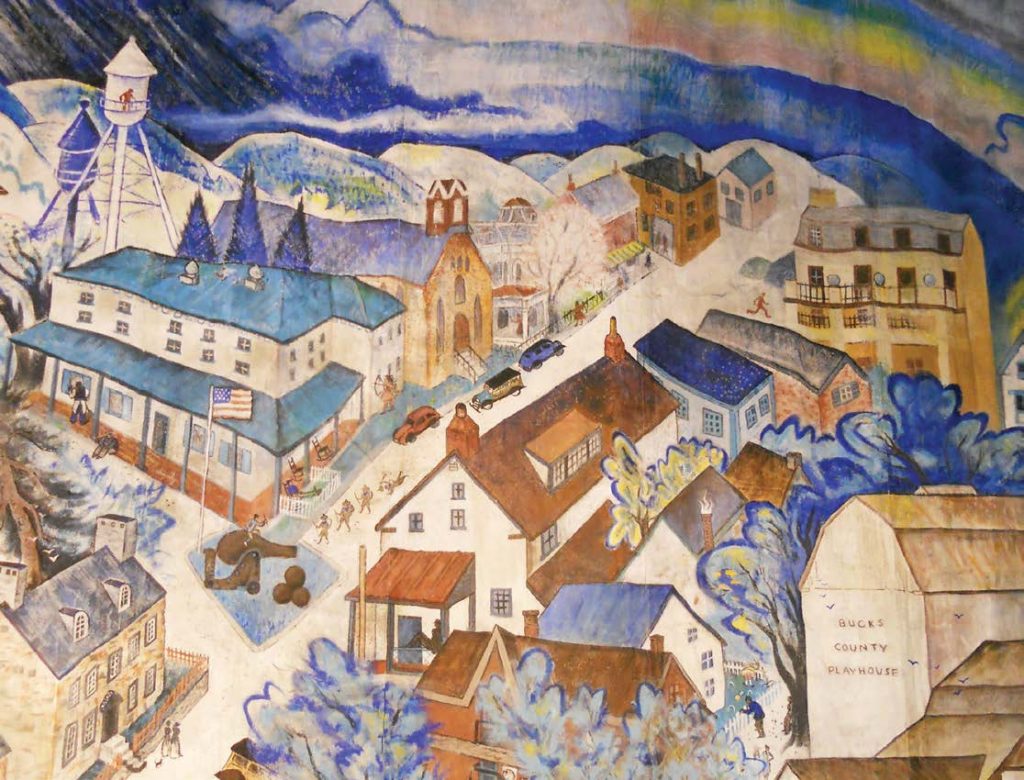

In 2012, EverGreene was brought in to restore the theatre’s historic fire curtain. In the 1930’s, Charles Child (Julia Child’s brother) painted the fire curtain for the Bucks County Playhouse on which he depicted the town of New Hope, Pennsylvania. Local landmarks are Bowman’s Tower the Logan Inn, and New Hope Railroad Station, as well as The Playhouse. Many aspects of the townspeople in their daily lives, including a nude sunbather and artists setting up easels, are painted around the landmarks to emphasize New Hope’s reputation as an artists’ colony.

The mural had been damaged by water and faded by time. Tears in the curtain overtime had rendered it very fragile and immobile. The distemper paint surface was soiled and there were numerous areas where the paint had flaked off. The rigging it was attached to was in bad shape, and moving the curtain could cause further damage to the surface of the mural. The curtain also contained asbestos in the substrata, and moving it- especially with the broken rigging- was very dangerous. Rigging experts were brought in to stabilize and carefully lower the mural to give our conservators access for treatment.

Extensive documentation of its condition, and testing to determine the best method of cleaning and repairing the curtain were done prior to its restoration. Our conservators got to work cleaning the mural with a gentle vacuum, dry conservation cleaning agents. The tears in the curtain were repaired, and the entire front and back of the curtain was sealed to encapsulate the asbestos, making it safe for public use, and preventing any further damage. Once the historic paint was isolated with a varnish, lost areas were filled in with reversible conservation paint. Missing information was not restored in full, but compensated tonally. Adding in any unknown detail was avoided to preserve the work’s integrity. We sought to enhance the overall aesthetic of the composition.