Architectural metals. A building’s jewelry, consisting of ornate grilles, panels, doors, cornices and sculpture – create visual delight through intrinsic and applied finishes. With the exception of iron, which is usually painted, decorative effects on metals are achieved with chemical patination, plating, coating and mechanical texturing to produce a wide variety of colors, patterns and finishes. Over time, however, the artistic intent can become lost through years of exposure to the elements, general wear and uninformed treatment. Restoring these often fleeting original finishes can be challenging, as they may leave little evidence behind. These challenges can be met through examination and analysis of the existing finishes on site, in the laboratory, and through archival research.

The intrinsic color and tactile qualities of architectural metals such as bronze, copper, aluminum, gold, lead, nickel, silver, tin, zinc and titanium are frequently enhanced through chemical manipulation and coatings. These finishes are superficial, ephemeral and, when left unprotected or unmaintained, subject to rapid deterioration from exposure or wear. Because patinas and plating on metal are considerably thinner than paint or varnish, they do not accumulate in a series of successive strata. Unlike paints, patinas will oxidize when exposed to the environment. The result is both a physical and chemical change in the patina that leaves no readily observable evidence of the original appearance.

Finishes on building exteriors are often lost to environmental exposure, while interior surfaces are frequently altered by repeated wear or aggressive maintenance. An historic finish may be replaced by a new one that reflects a current trend or a new owner’s preference or a generic metal finish that is easier and more cost effective to maintain. Either way, the elimination of evidence of the historic scheme is the same.

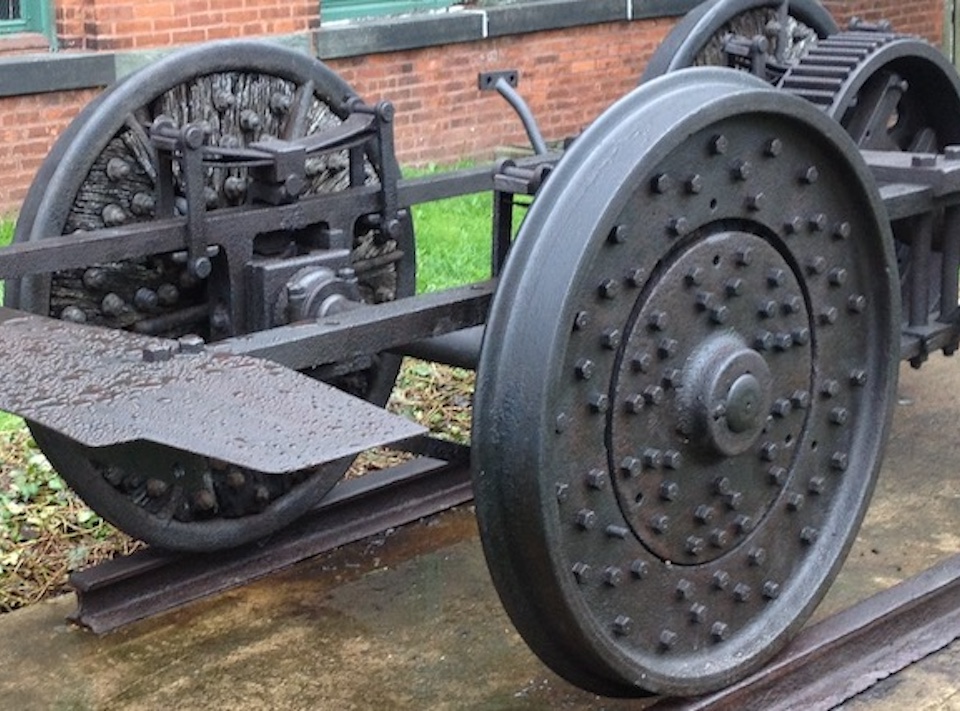

Our conservators partially disassembled one of the panel groups at the David H. Koch Theater, revealing evidence of non-original, field-applied finishes and illustrating general construction techniques. A cleaning test at the theater illustrates the corrosion and soiling that have accumulated over the original oxidized metal finish.

Looking for evidence. When an owner or building manager decides to preserve or restore decorative metals to their original appearance, the primary challenge is determining what the original finish actually was. At this point, a metals conservator can take on the difficult forensic task of identifying meaningful historic evidence and deciphering original artistic intent to faithfully restore these finishes. A systematic in-situ study of the metal elements, combined with a fundamental understanding of the methods and materials used to create the decorative finish, lays the foundation for a fruitful investigation.

Original finishes may be found intact in protected or concealed locations. On exteriors, original finishes may have become encapsulated within later construction or under paint. Finishes may also be found under hardware or inside complex assemblages, where they are shielded from oxidation, weathering and maintenance. Evidence may exist in peripheral and under-used areas, such as inside closets and pipe chases, above soffits and within stairwells. Light fixtures and other elements that are difficult to reach – and difficult to refinish – may also retain original finishes.

Careful cleaning, disassembly or removal of overlying elements can help reveal the original treatment underneath. Further sampling and targeted laboratory analysis can provide additional insight. Elemental analysis of a sample through scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) or X-ray fluorescence (XRF) can confirm the identity of the metal substrate and determine alloy composition. Raman spectroscopy can be used to interpret corrosion products and mineral pigments. Where present, samples of coatings may be examined via polarized light microscopy to discern the types of binders and pigments used. At the National Academy of Sciences, a conservator prepared a mock-up of several hot-applied patinas to demonstrate the likely range of original patina appearances.

Planning the restoration. Once evidence is identified and interpreted, developing a comprehensive restoration plan can still be extremely difficult. Forensic observations usually identify some, but not all, of the original finishes of a building-wide program. In the absence of conclusive evidence, an educated and experienced metals conservator will supplement physical with documentary evidence, including plans, specifications, historic photographs and written accounts. Archival evidence serves as a cross-reference for physical evidence, helping to establish probable timelines of intervention and to aid the reconstruction of likely schemes. This process can be aided by the use of digitally modified photographs and field mock-ups, to illustrate alternative finishes before selecting and specifying a final treatment. Treatment recommendations should consider the desired appearance of the finish versus anticipated levels of exposure and wear and also accommodate protective coatings.

The conservator can work with the client to develop reasonable goals and expectations for the lifespan of the finish, as well as realistic projections of the owner’s desire or ability to perform routine maintenance. This may include educating clients about the vulnerability and limitations of metal surfaces and the finishes that can be applied to them.

To a building owner, the loss or alteration of an original decorative finish may appear to pose great challenges. However, this challenge can be overcome by working with a competent conservator. Our portfolio demonstrates the advantages of engaging a metals conservator early in a project to facilitate an accurate and responsible restoration plan. The beauty, variety and subtlety displayed by a responsibly preserved or restored decorative metal finish are satisfying rewards to this partnership.