“Behold I am making all things new” – Revelation 21:5

The season of Easter begins Easter Sunday and concludes on the feast of Pentecost. In the Northern hemisphere, the season of supernatural resurrection (Paschaltide) coincides with new life in the natural world. Spring gives much fodder for contemplation of Paschal mysteries. How might Christians, a self-described “Easter people” keep this reality central at all times of the day and year?

St. Benedict’s answer was a rule of Ora et Labora (prayer and work) by which cloistered religious communities have lived since the 6th Century. A key part of the discipline is collectively praying the Liturgy of the Hours at set times throughout the day. For monks at the Benedictine Abbey at Beuron, Germany in the 1860s, praying the hours in the form of Gregorian chant was integral to keeping the heavenly reality ever-present. At the time the decadent Rococo and Baroque were predominant in the decorative arts, and the fine arts were dominated by highly representational artwork, which sought to portray things as they appeared. Brother Desiderius Lenz, a monk at Beuron, found these styles time-bound, overly emotional, and terrestrial – wholly inappropriate for contemplation of the hidden Kingdom of God. Admiring the serene, other-worldly qualities of Gregorian chant, Lenz sought a visual equivalent. His quest led him to a system of proportions used in sacred art thousands of years before the time of Christ.

“It seems to me that the Egyptians possessed the secret of moving the soul of man…and of awakening within him a mysterious awe.” – Desiderius Lenz.

Watch Emily’s AFR Conference presentation “The Imperial Majesty, the Monks, & the Moderns” for more on Napoleon’s Egyptian exploits, Beuronese art, and their influence on modern art.

THE SECRET TO MOVING THE SOUL

Egyptomania swept the 19th Century. Napoleon’s 1798 expedition to Egypt was a military disaster: British destruction of the French fleet left 35,000 soldiers and 167 scientists stranded. The marooned scientists discovered the Rosetta stone and documented the wonders of Pharaonic Egypt (3150 BC – 30 BC) with unprecedented precision. Soon allusions to ancient Egypt appeared on cigarette packaging, sheet music, parlor games, and the architecture of theaters, factories, and monuments across the globe. Desiderius Lenz attributed the power of the Pharaonic aesthetic to the use of a classical canon of proportions derived from the golden ratio.

Observable in plant life, the human body, and the cosmos, the proportions of the golden ratio (1:1.618… or φ) are widely understood as divine geometry – the underlining principles of God’s creation. To Lenz, the use of the Golden ratio in the Pharaonic canon suggested the information had come down to Ancient Egypt through the first man.

“Adam knew, must have known, all the secret depths of the aesthetic geometry of God – the laws of measure, number and weight…Seth or Enos were the first who began to prepare a special house for the worship of God…we must understand these men were the pupils of Adam. Hence, the oldest and first motifs of this art of the temple-building were those which we find in the ancient art of the Egyptians, in works dating from a time when the knowledge of God still existed…These principles, utterly simple and logical, present themselves as eternal laws, principles which will always be valid and will always retain their mission of educating mankind in what is true, leading them towards the eternal and above all making them receptive to the principles of authority, of eternity, of truth.” – Desiderius Lenz, The Canon

PRAYER & WORK

Along with fellow Benedictine Gabriel Wuger, Lenz established the Beuroner Kunstschule (School of Beuron). Flat, serene, symmetrical, and heavily dependent upon line, the Beuronese style is distinctive and compelling. Like chant, making the artwork is a spiritual practice by the community of monks. The Egyptian stylistic influence can be seen at first blush; what may not be immediately apparent is the internal geometry of each constituent part of the composition.

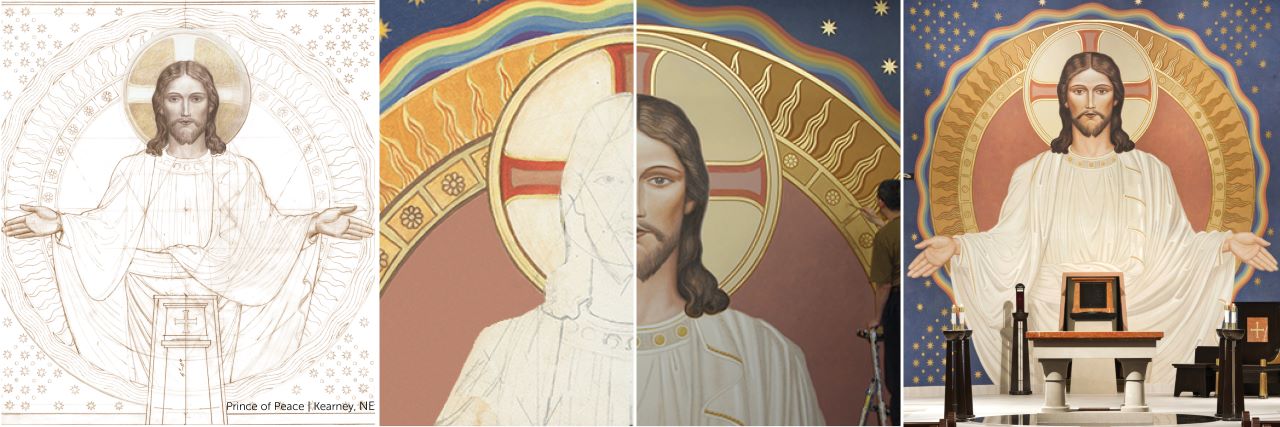

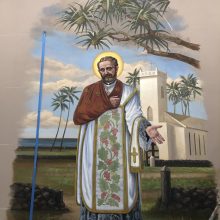

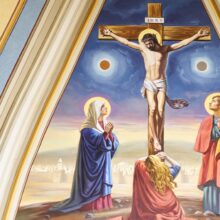

Abbeys graced with works by the Beuroner Kunstschule include: Beuron and Rüdesheim am Rhein in Germany; Emmaus in Prague (destroyed in the allied bombings in WWII); and the order’s Mother House in Monte Cassino, Italy (severely damaged in the bombings but restored). Some of the best-preserved original Beuronese murals can be found in Conception Missouri, at the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception. EverGreene was privileged to participate in the conservation of these powerful works in the 1990s and later collaborated with the brothers at Conception Abbey to create new murals in the Beuronese style in the refectory and chapter house. It was an unexpected treat to discover historic Beuronese murals at St. Anselm’s Parish in the Bronx, NY, and when Prince of Peace Parish in Kearney, Nebraska constructed a new church in 2011 they commissioned murals in the timeless Beuronese style.

OTHER-WORLDLY IMMERSION

In the Beuronese tradition the same geometric principles applied to murals guide the design of vestments, statuary, and liturgical furnishings, each element possessing interior geometry. Designing everything used in the liturgy embodies Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). The effect, particularly when alive with chanted liturgy and incensation, is immersive and otherworldly. To interact with works constructed with these principles is to meditate upon reunion with God’s will, which is at the heart of the Pascal promise of eternal life with Him.

Author: Emily Sottile, Director of Sacred Space Studio.

Acknowledgments: Brother Michael Marcott, Brother Anselm Broom of Conception Abbey, Eugene Nikitin, Senior Designer at EverGreene, and the writings of Bob Brier and Peter Brooke.